Back to Journal

Bach arranging and arranged: an interview

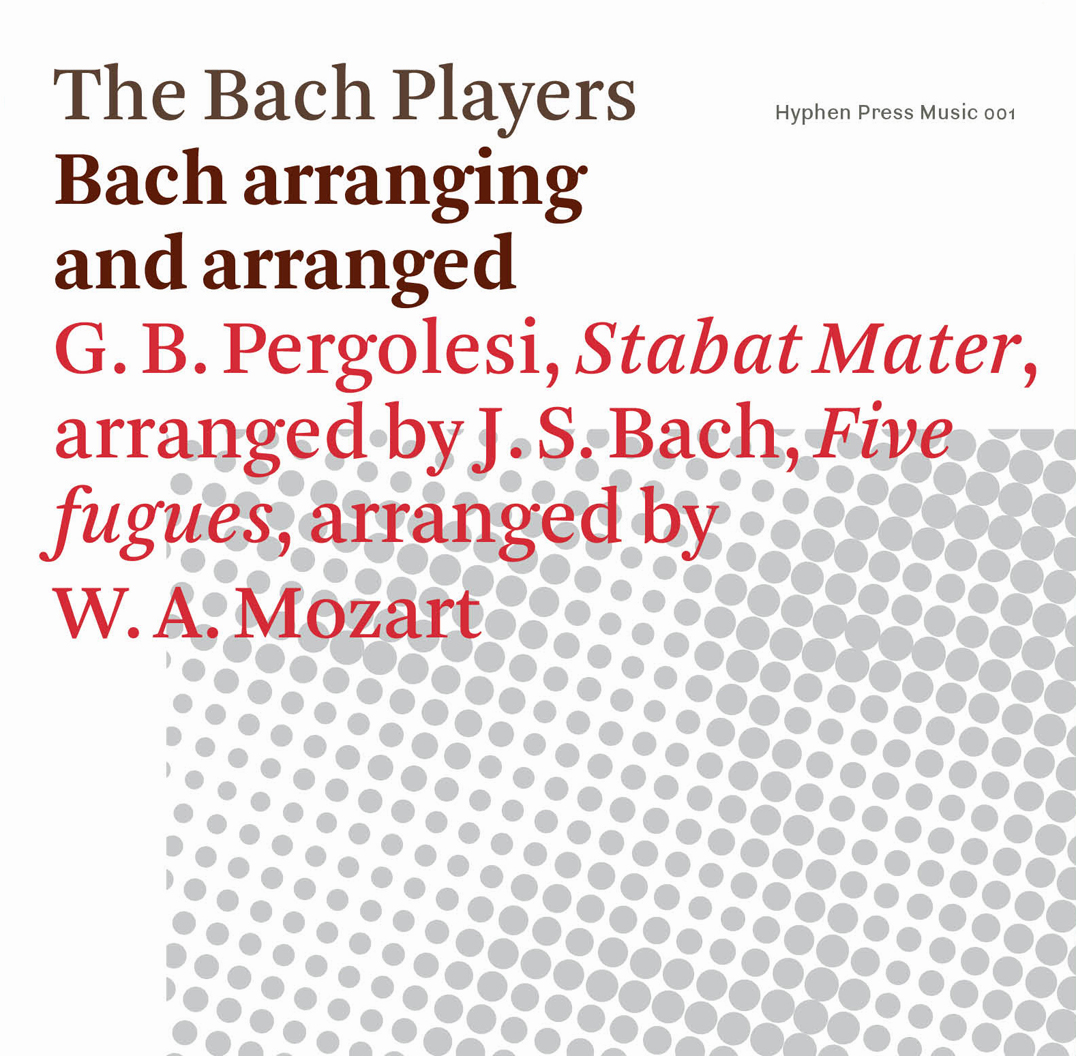

In this conversation Nicolette Moonen, artistic director of The Bach Players, talks with Robin Kinross of Hyphen Press Music about the background to the group’s first recording.

RK: Why this programme?

NM: I had the Pergolesi/Bach piece in my library for quite a few years and it intrigued me – but it just lay there. When we decided to start the new series at St John’s Downshire Hill it seemed a good idea to do something which was not widely known and with a connection to Bach. This took us to the Bach fugues arranged by Mozart. We had already done many fugues in our programmes, and these arrangements by Mozart we had played in concert the year before. We wanted to do them again. So we were now doing Mozart, and we made the step of including a Haydn quartet (op. 20, no. 5) in this programme. We were then making a programme that bridged our history of doing Bach’s cantatas with wanting to play Haydn’s chamber music, with his string quartets at the centre. We chose that particular quartet because it ends in a big double fugue. The programme worked as a good way to launch a new series, with new ideas, but with some continuation of what we had done before.

RK: In the process of looking at the editions you discovered that the Pergolesi/Bach was more complicated than it seemed.

NM: As well as the new text, one of the main features of Bach’s arrangement is the rewritten viola part. This gives it a special flavour: more German than Italian. It became clear that one couldn’t play this piece as if it was Pergolesi. It has a German text, and Bach was very precise in changing the speeds of certain movements to fit the text. Actually it isn’t an arrangement, it’s a parody – that’s something different. We had to try to look at the piece through Bach’s eyes.

RK: ‘Parody’ has a negative connotation; maybe this is a palimpsest? One piece written on top of another?

NM: With the fugues it’s clear: these are arrangements of keyboard music for string quartet. In the Pergolesi arrangement the scoring is the same – for soprano, alto, strings and continuo – but Bach uses a completely different text, in a different language, and adds to the music. It’s surprising how well, in many of the movements, the text works. There are a few movements where we struggled with the text – we felt the music and text didn’t really go together – in these movements Bach changed the tempo indication from Pergolesi’s.

We don’t know if he did this for a special occasion, or just for his own pleasure and interest. He did it at the end of his life. He must have seen that Pergolesi was forward-looking, and we all wonder how Pergolesi’s writing would have developed, if he hadn’t died so young. I can hear Mozart and Gluck coming …

RK: With the fugues you were able to do something special too: to play the one that Mozart hadn’t finished, and then to make arrangements of those that Mozart hadn’t done at all.

NM: Looking at the fugues in the Well-tempered Clavier II, we saw that if we added just three more fugues we would have a collection of all the four-part fugues from that work. Rodolfo [Richter] suggested that he could arrange these three for string quartet, in the same manner. But there is a difference: Rodolfo used the so-called Urtext of Bach; while we now know, from Yo Tomita, that the WTC edition that Mozart used was not faithful to Bach’s original score. It shows how soon after someone has written something, then editors start changing it. Yo Tomita’s position with the Mozart arrangements is, very correctly, that one should respect what Mozart wrote.

RK: I have the feeling that in such things you are living up to your claim for the group, that it works with ‘a genuine spirit of enquiry and reassessment’.

NM: Especially if you are going to record, then you do have to look into things. Also we had the luck of taking about nine months over this project, from the first concert in September to another performance in May and then the recording in June. During this time I had found Yo Tomita via the internet – and he is the man who has done the necessary research. This is the fun of the process.

RK: Now for a larger question: why record now, more than ten years after the group started?

NM: When we started, I did look into recording and tried to find a company. This was 1997 and it was already the beginning of the decline of the classical music CD industry. Although at that time there were not as many Bach cantata recordings as there are now – and our emphasis was very much on Bach cantatas – there were already enough on the market. I decided not to put my energies there; I thought that there wasn’t much point in duplicating existing recordings.

It was only after moving to a different part of London – finding a new home for our concerts, beginning to play a different kind of programme – that the idea of recording came up again. In conversation with you, we mapped out a series of recordings of programmes that have a theme behind them, rather than being collections of pieces by the same composer. This lets us play Bach cantatas in fresh contexts – now linked to wider themes and to works by other composers. One might listen to the whole of one of these CDs as one listens to a concert, and for the pleasure of finding the connections, rather than just listening to the one piece on the CD that you want to hear. We decided that the only way we could go was with total control of the recording and the presentation of the CD.

RK: This fits exactly with what I’ve always believed: that someone (a publisher) has to make a leap of faith and say ‘this is what we are doing’. You don’t try to rationalize it with some attempt at market research.

NM: You mean there’s no commercial idea behind it?

RK: There should be. But the first decision, of whether or not to make this work, is based on instinct. You have to say ‘this is what we’re doing, let’s go for it’. It’s good to be honest about that.

NM: That’s how your books are made?

RK: Yes. You have to be clear about what you are doing and hope that people will become interested and want to follow you.

NM: From our side, we are hoping that, by being published by a book publisher, we’ll attract people from other spheres – that we don’t stay confined to the Early Music world.

RK: Equally, from our side, it’s an opening up in a new direction.

NM: Your first link with music has been the book of interviews with Morton Feldman …

RK: I can go back to the beginning and to Norman Potter, who is the father figure behind Hyphen Press. Norman would always say that music is the most important, the most essential art.

NM: Why did he say that?

RK: I think because it touched him more deeply than any other art. But also for the reason that music is more essential, more abstract. Like architecture, it has structure and form. But then it’s pure sound, immaterial.

This interview is also published in the CD booklet, along with a brief history of the phenomenon of arrangement by Hugh Wood, and a discussion by Yo Tomita of Mozart’s arrangements of the Bach fugues.