Back to Journal

Interview with Jaap Schröder

Jaap Schröder died on 1 January 2020, the day after his 94th birthday (he was born on 31 December 1925). Jaap was my godfather and my teacher on ‘modern’ violin during my studies at the Amsterdam Conservatoire in the 1970s. Our families lived on either side of the Vondelpark in Amsterdam. Jaap had a French wife – Agnès – and so did my father Frans Moonen, who was also a musician. Both couples had families of three girls. Some of us went to the same secondary school, the Spinoza Lyceum. We have always stayed in touch. Nicolette Moonen

In February 2012 Jaap came to London to attend to small business matters and stayed three days with us. We took the opportunity of recording the interview that follows. We envisaged this as one of a series of interviews with musicians of the older generation. Our conversation with Jenny Ward Clarke was published in 2015, here.

This interview took place in the late afternoon and evening of 7 February 2012. As will be evident, Jaap hardly needed prompting to speak about his life. After some time, we agreed to pause and went to have supper in the local pub. But Jaap still had more to tell. We sat down to talk again, turned on the recording machine and did another session.

The recording lay untranscribed for some years. Eventually we made a transcription and sent it to Jaap for his comments and corrections. He was always busy and often travelled, late into his life, and he did not react to it. Some years later on we met again for a meal in Amsterdam, and gave him a printed transcript, asking him for corrections. He glanced at it, remarked on a small error in the transcription, and said that he would look through it and give us detailed corrections. But he never did this.

Now that Jaap has died it feels appropriate to publish this document. The text contains a number of points that are uncertain. If any readers can help to clear these up, please do get in touch. We would also be glad to add photos of the people or music groups mentioned and would welcome help with this.

Nicolette Moonen and Robin Kinross

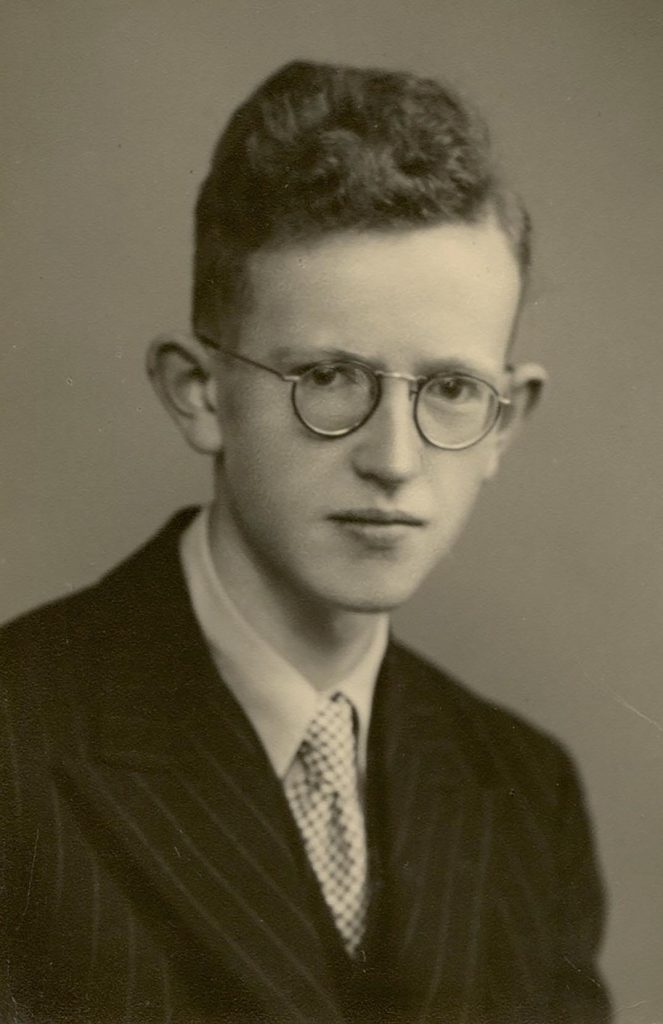

As a young man (photo: Schröder family archive)

Beginnings

N: You trained on what we call the modern violin, like everybody else at the time, and then you somehow got interested in baroque music? What set you off on this journey?

J: I think part of it was that I am not a student of the Dutch violin school. The Dutch violin school, for people who had some talent, was always Oscar Back. There was Willem Noske also. But apart from [Herman] Krebbers, and [Theo] Olof of course, it was Oscar Back. He was the saint.

N: Even when I was a student, it was still Oscar Back.

J: And then Jean Louis Stuurop, who suffered from this. He was the last, I think, who was trained by Oscar Back.

N: So, who did you train with?

J: I went to the Music School in Amsterdam – so, before the Conservatory, though it was in the same building (Bachstraat 5). I went there for my first lessons with a demoiselle, juffrouw Jung. Then she left, for a Carmelite monastery, and I became a student of Julius Röntgen [1881–1951], the eldest son of the well-known composer, Julius Röntgen [1855–1932]. Not a very good teacher, but a very nice man.

I was playing for fun at home. My mother played the piano very well and with great pleasure, but her parents never allowed her to become a professional. She was born in 1900, so she belonged to that generation … We always listened to her. I usually played with her, and with a few people who came around. I loved playing the violin, with lots of repertoire. It was really chamber music – quartets. I played with different people in town – doctors and so on. In 1943 I graduated from the Vossius Gymnasium, in the middle of the war.

What to do? I was thinking: the violin – playing quartets is one thing, but what are you going to do at university? Well, I thought history or musicology, classics. But the Germans controlled the university. You could not go there unless you signed a declaration of loyalty to them. They were the occupiers, and I didn’t want to do that – I couldn’t. Since I was already studying with Julius Röntgen, who was also a teacher at the Conservatoire, I said that as long as the war goes on I will continue the violin. Curiously the Germans never set foot in the Conservatoire. They controlled the university, but the Conservatoire was just ‘stupid musicians’ – not interesting or dangerous.

So, I simply continued in a more professional way, with solfège and so on. I met a lot of nice people. Willem Andriessen was the director.1 His brother Hendrik taught analysis, a wonderful man. Ernst Mulder was the harmony teacher. I had a great time, I loved it, and when the war ended, I wanted to finish, which was logical. I had already spent two years there. I finished in 1947. Four years of professional study.

I was out almost every night playing string quartets. There was this Wim ter Meulen [?], a banker, who had a beautiful house on the Jan van Goyenkade, and I played for years and years with him on the second violin. He was not a very good player. He played a beautiful instrument, an Amati violin. I remember that his technique wasn’t up to standard. Also, he would smoke a pipe while playing. He was also the host of the many foreign quartets that came to play at the Concertgebouw. For example, the Trio Pasquier were his guests – I went with my father to those concerts – and the Quatuor Calvet. Joseph Calvet had a second ensemble after the Second World War. There had been a famous Quatuor Calvet, which disbanded in 1940 before the beginning of the war. But these were younger people and it was a very good quartet.

So, Calvet stayed with Wim ter Meulen, and listened to our playing and gave us hints and so on. It was very nice. I don’t remember the details, but I talked with him about what I admired – his playing and Pasquier’s – and he said: ‘Oh I can help you if you want a scholarship to get there.’ That was the Maison Descartes [now the Institut Français des Pays-Bas], and he knew the people there. Thanks to his help I got a scholarship to go to Paris for a year. So, you see it is a completely different picture from the virtuoso-trained people who were only playing the Tarantella by Wieniawski …

N: But I thought that the Paris Conservatoire very much trained people in that way, as soloists.

J: Probably, but I was at the École Jacques Thibaud.

N: And was the programme different there?

J: It is a school especially for violinists and pianists – Marguerite Long and Jacques Thibaud. It still exists. I got a teacher: Jean Fournier, the brother of Pierre. He was a good teacher. I heard him play a bit and later I met him in Salzburg. He gave me the French repertoire especially: the Saint-Saëns Concerto, more Isaye, Lalo’s ‘Symphonie espagnole’ and then finally the ‘Tzigane’ by Ravel. And then at the end of that year I was permitted to represent the school with the pianist of that year, Daniël Wayenberg. We played the Ravel ‘Tzigane’. I got the first prize. I was happy, but I still had in mind that I wanted to get to know the Pasquiers. And I met them several times. Jean, unfortunately, did not really teach. He was playing. They made long concert tours outside France. They went almost every year to America. Fortunately in that year 1948/1949 he was not very much away from Paris and he was willing to have me; so I came to his home for lessons. Sèvre Ville d’Avray, between Paris and Versailles (I would get to know that train-line very well). By then, of course, the scholarship was no longer there. My father was quite willing to help. I stayed at the Cité Universitaire, at the Dutch College and I didn’t spend much money. I was thin as a string bean.

N: I would like to see photos from that time!

J: I did eat well. I didn’t suffer at all. My father said at that time: ‘How do I send you money?’ To change guilders into francs was still strongly regulated. And then providence intervened again, because the Quatuor Calvet had a young cellist, Manuel Recassens. I have never heard of him since. He was a good cellist, and a nice fellow. And Recassens had discovered a wonderful cello at Max Möller’s.

N: So, he had to go to Amsterdam.

J: He wanted to buy this cello. We are probably talking about much more money than I needed. But, in any case, my father would pay Recassens in guilders and he paid me in francs. So, that’s how he financed me for the second year.

I was there two years, and enjoyed it tremendously. Jean Pasquier’s way of handling the bow, of talking with the bow … I am not at all a Dutch violinist in that sense.

N: Of course, that’s it. Are there old recordings of Pasquier?

J: I have an old recording at home – I have to listen to it again: Adagios and Fugues by Bach / Mozart. And they certainly recorded the Mozart Divertimento. I haven’t listened to that since I was in Paris. It may well be that I feel that I have developed or changed since that time. Though I am still inspired by what I learned from him.

N: Interesting that you say he had this way of talking with the bow.

J: I always looked at his bowing when he was playing. It was so marvellous – his flexibility. It was not a question of power.

N: Was Oscar Back very much about power?

J: Well, not especially power, but in any case his style of playing was so different. It was based on the Central-European style. It was very different. And that taste – I didn’t care for it at all.

N: So, that got you started in Paris.

J: That’s how I became a different violinist, and I combined this with my love of Baroque chamber music – Telemann and Vivaldi. At my secondary school there was a music club, and we came together. There was a flute player, Hans Mackenzie, who later became a vicar. I remember my mother becoming furious because Hans played the flute in our house and the condensation water from his flute fell in the sugar –

N: Not nice! So, you discovered Telemann already during secondary school?

J: Sure. And some French music – eighteenth-century music. Of course that was possible. And then Mozart Sonatas with my mother.

Röntgen left during the war. He had family behind the IJssel Line. It became very difficult in 1944. The winter was coming and the Germans were not leaving. We had this hope in September 1944 that the allied troops would succeed in Arnhem – the famous troop landing over the bridge. Well, that was a disaster. The Germans had more troops than was imagined. So instead of being liberated in September, we had the most terrible winter of the war. Julius Röntgen just managed in time to get to family in Overijssel, behind the IJssel, where there were more things to eat. So then his students were taken over by Jos de Klerk, the Belgian teacher. He was a very solid teacher, a technician. I am grateful to him, for his teaching. He did not have a musical profile. But that was before I went to Paris.

Paris

N: Do you feel that the Paris years were the really formative ones?

J: Yes, for the musical side. Of course with De Klerk I studied the Brahms Concerto and Chausson’s ‘Poème’ – what a wonderful piece! I played it for my final exam.

When I came back in 1949, Agnès was in the picture

R: When did you meet Agnès?

J: Well, that is a special story. I was living in Paris. Agnès had a sister, Madeleine, who was married to a Dutchman, André van Dam. On 23 December 1948, Agnès took the train to Rotterdam, and I sat in the same train going to Amsterdam. So, I didn’t meet her in Paris. We went back to Paris after Christmas and met again there. And then of course I went to Versailles and met her parents: very nice people, but rather conservative, I would say. So Agnès had a different education from me. L’abbé [Daniel] Joly, the priest there, married us in 1950.

I am very much connected with that. L’abbé Joly used to invite famous people – theological specialists such as the Dominican Yves Congar, who was the special advisor at the Concile, and Henri de Lubac, who was a Jesuit. These people were suspect in Rome. Teilhard de Chardin came, invited by l’abbé Joly. It was an incredible atmosphere of intellectual enthusiasm. I still stick with this.

We were engaged in the spring of 1949. Agnès was already studying medicine. We had planned the wedding for 1950. During that year I had to look for a job. I was lucky again, because I found that the Radio Kamer Orkest [radio chamber orchestra] needed a section leader, which I accepted. For one year I was leader of the second violins. Then I got an offer to join the Kunstmaandorkest under Anton Kersjes. Then the RKO was sad that they had lost me, and they asked me back with a better salary to be the concert master.

I was still living with my parents on the Rooseveltlaan. When we married, at Christmas 1950, I had managed to find – it was difficult – a little attic apartment in the Admiraal de Ruiterweg, with an old lady who had these rooms available. Fortunately that lasted only a couple of months, because then we were able to move. My brother-in-law, André van Dam, who had married Agnès’s sister, knew Herbert Perquin [actor and cabaret artist] and his wife and they were leaving for another home and they had lived in the centre of town, Olofsteeg 4. And that was fantastic. The house dated from 1659 – close to the station, because I went to Hilversum every day, so I walked 5 minutes. We had a wonderful time there and two of the girls were born there, though not at home. Cécile was born in 1959 and by then we were already in de Gerard Brandtstraat.

So I continued my work with the orchestra, but was asked fairly soon – yes, that was by juffrouw Schill [Maria Elise Schill], head of the Nederlands Impresariaat, which organized a violin competition for young people. At first I didn’t care for it, but then finally my father said ‘why don’t you do it?’ So, I participated – I don’t know what I played – and I didn’t win the first prize, but the second. The first prize went to a violinist who went to America, Kees Kooper. In the jury was Nap de Klijn and he picked me because they needed another second violin in the Nederlands Strijkkwartet.

N: Ah, that’s how that started.

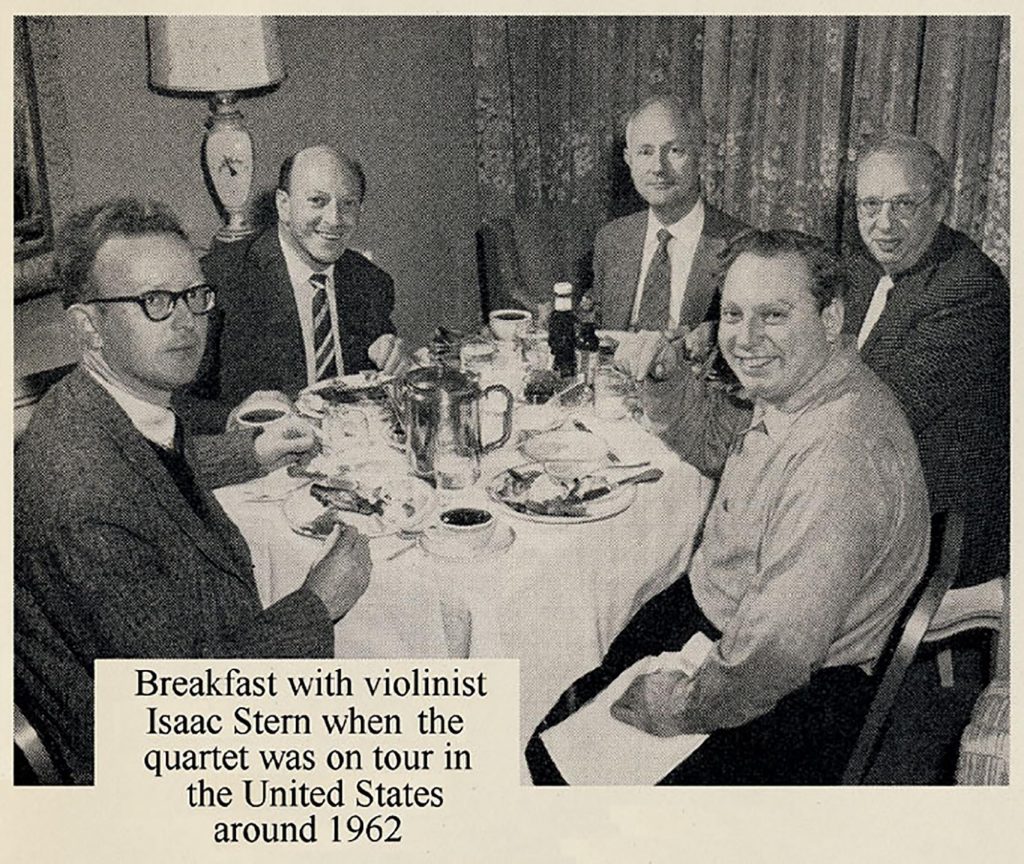

Around the table: Jaap Schröder, Nap de Klein, Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp, Paul Godwin, Isaac Stern (photo: Schröder family archive)

The Netherlands String Quartet and Paul Godwin

J: It’s curious how the right moment comes for the right thing. Johan van Helden was the second violin, and for some reason he left the quartet. So, they needed another violin. And oddly these three musicians – Nap de Klijn, Paul Godwin, and Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp – were about 20 years older than me. But I was very happy to accept that. I was still with the orchestra. Each of us had his own job. We rehearsed in Bussum, where Boomkamp lived, in the evenings, after the orchestra. Perfect, because with the radio orchestra there were never concerts in the evening. So, I spent many evenings in Boomkamp’s house. He had a a big room with all these instruments, which he later sold to the museum. I was a member of the Quartet from 1951 or 1952, and then already in the second year we came to England for the first time. After 1952 we came many, many times. So, when I tell details I don’t always remember the right chronology.

So, I started with the quartet and that was wonderful: especially the later repertoire with Paul. I was sitting next to him. Paul Godwin was a wonderful musician. He was of course from the Central-European background [originally, Pinchas Goldfein]. He was the most marvellous ‘Stehgeiger’– a stand-up violinist. He had a career in Berlin in the 1920s. He was a child prodigy and studied in Budapest with Jenö Hubay, and then went to Berlin. He was a buddy of Gregor Piatigorsky, they studied together, and they were thrown out of the conservatory together because they had jobs outside the institution. Later on we visited Piatigorsky, in Beverley Hills, Los Angeles. It was wonderful.

Paul had a way of playing. It was of course not at all the French school, but it was so … part of my inspiration came from him. He survived the war because his wife was not Jewish. He himself had to work at Schiphol, carrying stones and so on. The other Dutch people who had to work there knew him, of course, because he was famous, and they took as much as possible from his hands. So he came out of the war. Nap de Klijn asked him to play the viola in the quartet, which he had never done, but he was a wonderful viola player – wonderful. Then in the radio we got a contract for different ensembles. The VARA [‘Vereeniging Arbeiders Radio Amateurs’] engaged him. For years he had these regular ensembles: the Waltz ensemble, the Hungarian, the Russian – all that.

And his wife Friedel recorded many of these and after the VARA label issued a number of recordings, LPs. And then my friend Henk Knol, who was the viola player in the RKO, made many of the arrangements for Paul for what you needed: two violins, viola, cello, and piano. The pianist was an old friend of Paul who was also from Eastern Europe, from Vilna, Isja Rossican. He was a Tonmeister in the radio, but a fantastic pianist and a nice fellow. I loved them a lot. So besides the orchestra, I had the quartet and I had these recordings with Paul. Every two weeks we had a programme to record in the VARA studio and they were always half-hour programmes, which we worked on for six hours. So, in six hours we produced a half-hour programme with short numbers. You never heard it?

N: I don’t think so, but I would love to hear this.

J: As a young fellow, Paul was in Berlin. He was not only an excellent player, he was successful: he had orchestras in four different hotels. So with his car and chauffeur, he travelled from one hotel to another, to the next orchestra, and played again, also for the dancing, and during the night he made recordings. He made thousands of recordings for Polydor. They must still be somewhere. He made a career with that in the 1920s. And he married the daughter of a violin dealer; as a wedding present his father-in-law provided him with a Strad. That was fantastic.

Now we come to the terrible thing. The Nazis came and he had to flee. More than that: before this, his father-in-law, who was a Nazi, obliged his daughter to divorce the Jewish Paul. So, he had to disappear from Germany in 1933. He could have made a fortune. Of course, he had a fortune there, but he had to flee without much money, though he took the Strad with him. All his life he played that Strad, which is somewhere in Holland now, part of a collection of instruments that was supervised by Everard van Royen. So, then he came to Holland and played in Western Europe – he played also in Belgium and in France, in the spas, where there was entertainment music. And in the Kurhaus where there was entertainment with Dutch musicians. That was first level – playing this music with his Strad. I have learned a lot from him.

I am glad that with the Nederlands Strijkkwartet we recorded Mozart and Haydn. It was an excellent quartet. We had a lot of success in America. But the best we did was the Dvorak, I thought. It is our only recording of romantic music which has survived. We travelled in Europe, we went to Germany: Paul found back some old friends in Berlin. He was happy to do that. And we went to England every year. Our first trip to America was in 1958. In fact it was a trip that was organized by an American, Columbia Artists Management, for Nap and his wife. This was a pianist, Alice Heksch: a wonderful pianist and a wonderful woman. She had died of cancer just before we went. Nap had played a couple of recordings with her, and concerts in Western Europe, and had this invitation to come with her to the States. It couldn’t happen. They changed the contract – he offered the quartet. So the quartet came in February 1958 and after that we went almost every year.

We had a great career in America. I know most of the States – I love America. At that time of course the whole situation was different. I lived through many historical moments. When Kennedy was shot I was travelling between Boston and New York State, and I saw the flags going down. I thought: ‘What is happening?’ Then a few days later when Jack Ruby was murdered, I saw that on television in New York. So many, many things I lived through there.

N: How would you travel there?

J: We flew with KLM. The first time, it was special, of course. We got articles in the paper: ‘Dutch ensemble going to America’. We went first to New York and then on from New York. In fact our first concert was in Canada, in Ottawa: Ladies Music Club. We travelled by car. It was all organized of course. The whole trip was scheduled by the management. So, we had to pick up a car and drive to all these concerts; and longer distances by train. I loved train rides. So, we started in Ottawa, then in Quebec, in February – it was winter – and then in New York in Carnegie Hall. So, we had a very good start in the Carnegie small hall. And we met the Amadeus Quartet many times – we were friends with them.

The Netherlands representative was Max Tak. He was a violinist and organizer and representative of the Dutch government. He was a member of the Concertgebouw Orchestra for a certain time, while he also had his own orchestra, like Paul Godwin, but on a much lower level: he played in Tuschinski [the movie theatre in Amsterdam]. By then the cinema was no longer silent, it was with music during the film or before the film. Max Tak and his orchestra were well known. We knew him before we came, and then he helped us there and did a lot of things for us. The famous story is about Mengelberg. One day he was in a talkative mood and during the intermission he said said to Max: ‘Ah, Mr Tak, I know about all you are doing here, in the Tuschinski and all that. I think you are wonderful. Also I wonder: How do you manage with the schedule here in the Concertgebouw – the rehearsals, I mean. When do you sleep?’ And Max answered: ‘During the rehearsals!’

We sometimes rehearsed in Paul Godwin’s house in the Achillesstraat near the Stadium. His wife Friedel died [in 1971]. He had remarried a German woman just before he had to flee. She was from Posen, East Germany, which is now Poznan in Poland. A very warm-hearted, kind person. They didn’t have children, but he loved children – he loved our children. And then she died. But then he was really a child. He was just working for his music. He worked night and day to perfect his fingerings and this whole repertoire with tango, csárdás, and all that.

So, that was a wonderful career with the Netherlands String Quartet, between 1952 and 1969.

I started then to play with Frans Brüggen. He was playing the recorder, of course, with lots of success. We played together in school concerts. In Holland there was an organization for these little half-hour concerts, with explanations. So with a small car we travelled to all of them. This was with Janny van Wering [harpsichord player] first of all. And then I was asked to participate in some concert by Utti [Gustav Leonhardt] and his group. This started at the end of the 1950s, I think. The Leonhardt Consort, with Marie Leonhardt and some other people you may know.

I had known her [Janny van Wering] because many Dutch musicians came to Paris to the Dutch house where I lived. So I knew Theo Bruins [pianist and composer] that way. He came to Paris to study with one of the famous teachers [Yves Nat]. He died too young. And Gerard van Blerk with whom I studied in Amsterdam; he was a very good pianist. He told me that he was asked by a doctor in Amsterdam, who was an amateur violinist, to come and play some repertoire with him. So they played Mozart, Beethoven – you name it – for a year or more. The doctor always called him and said: ‘Next time, so and so’. Then one time, he didn’t get any call. So he said: ‘Maybe he is ill – I will call him’. And so he called the doctor and said: ‘Sorry to ask you, but are you all right?’ The doctor answered: ‘Oh, I am fine, but we have played the whole repertoire. We have played everything.’ Yes, that’s the amateur mentality. The little book Das stillvergnügte Streichquartett [by Ernst Heimeran and Bruno Aulich] gives funny stories about how amateur string quartets work together, and then an appraisal of all the quartets in the repertoire. Of course we all knew that book.

My first quartet was at the gymnasium. I came to the school in 1937. So in 1939 I played my first quartet, with the physics teacher, who was a cellist, and two former students of the gymnasium, Conrad Muller, who became a professor of theology, and Dick Scheltinga Koopman, the co-rector of the Spinoza Lyceum.

N: I do remember him. He was mad about music, Scheltinga Koopman.

J: Yes, he was a good violinist. So, that was my very first quartet: the G Major of Mozart. But I knew the whole repertoire already, playing with all the doctors, so it was not a problem. We were better than just amateurs. And when I came to the conservatoire, of course I wanted to make a quartet again.

In those years I played with Bouw Lemkes, second violin, and Pem Fransen [?] was an old friend, he was the eternal student, a medical student. He did all kinds of things except studying. And he played the viola: he was asked everywhere, of course, because there were no viola players. And Françoise Vetter, the cellist, a very gifted girl, a strange person. She has lived in the USA, and has been in different orchestras, also in the National Symphony in Washington. Then she moved to South Africa and has been playing there. When she came to Holland a number of years ago she came to see me again. We had a very good quartet.

After 1945, when we could travel again, we played a few exchange concerts with the quartet, as representatives of the conservatoire, with Gent and I think with Brussels. The one thing that I remember is the Quartetsatz by Schubert (which we have just recorded with the Skálholt Quartet). That was really the best I had done until then. Then I went to Paris. No chamber music. The only chamber music I did in those two years was with a gamba player, Jean Schrick. (His son [also Jean?], I knew later. He is a baroque violinist who lives in Angoulême.) But this Jean Schrick was eager to invite me to his home and to play baroque music. But that was all.

Of course, with hindsight you can see the Trio Pasquier. They played in Paris, but they were not that successful. I mean, they were not playing everywhere in France. They made yearly trips to the USA and in Amsterdam they played regularly, but not that much in France.

N: Often people are more known outside their own country.

J: Yes. But still there were some well-known quartets. The Loewenguth Quartet was a very good quartet. And then the Pascal Quartet with Léon Pascal. He was the viola player. He was also the viola player in the first Calvet quartet. That broke up in 1940 and then later he started with the Pascal Quartet. When I was in Paris I heard many different quartets.

There was also the Hungarian String Quartet with Zoltán Székely, who was a Hungarian violinist but he lived in Amsterdam. He taught at the Conservatory. I bitterly regretted that I was not a student of his, because I admired his playing – a fantastic player, but not only that. Later I knew him very well: such a modest and unassuming virtuoso; living for his quartets. He had married a Dutch girl from a very wealthy family. He was the same age as Paul Godwin. Perhaps they knew each other in Budapest – I don’t know. He was after the same Strad violin, before it went to Paul, but he had a wonderful Strad in any case provided by his wife. They played in Paris: Salle Gaveau, a good music hall.

My utmost admiration went to Pasquier and then to Zoltán Székely. But now when I listen to recordings – not Pasquier recordings, because I don’t have them – but the Hungarian String Quartet: they are a fantastic ensemble, and especially for the tone production. When I listen to a modern string quartet, I think: no … don’t do that, be more sober. But Székely was the best I could imagine at that time. I loved him, because he was talking about the music, not about his career. You know, the Bartok violin concerto was written for him. He played with Bartok in Hungary when he was a young man. Bartok had chosen him for concerts there.

Bartok lived in Paris and then he composed his violin concerto for Székely, who was in Amsterdam teaching. But he refused to come to Amsterdam, because he didn’t get along at all with Mengelberg: too different in character. So Székely was studying this violin concerto. Maybe he went to Paris once and then continued working on it. Finally he called Bartok and said: you have to come, because in the first movement there is a whole section that goes until the recapitulation, which has some things that are not violinistic. You should change that – and so on. Bartok from Paris answered him: I am not coming, but I give you permission to do whatever you like. And so, in fact there are at least eight bars in the Bartok violin concerto before the recapitulation, which were written by Székely. But he never let it be known. Until I bought a book in Canada, in Banff where he lived, written by a cellist from nearby Edmonton, and who interviewed Székely and who wrote a book about Bartok and Székely. I learned this from that book. Székely was also a composer. He wrote a sonata for violin solo, and more than that.

N: That’s why probably Bartok felt he could safely say ‘you change it’.

J: Yes. Székely travelled with his quartet, and then after the war he settled. He became quartet in residence in Boulder, Colorado, and he travelled from there through the whole of America, until the time when they stopped. One after the other, they left or died. Székely settled with his wife in Banff, which is a wonderful place: the Canadian Rockies. And Banff became a music centre with a school and a festival. I have been there several times to teach and play and met Székely then on a private basis. We always talked Dutch together. He was such a wonderful fellow.

He was 93 when he died. His wife died before him. She was an Alzheimer patient and he took complete care of her, while he was still coaching ensembles there. He was the maestro living there: a revered master. So, we talked about all kinds of things. He knew a bit about my career. He said: ‘I will tell you something interesting. What I do every day now – I work on the Bach solo Sonatas. All these problems …’ And he started to share it with me. This man was such a wonderful personality, besides being a wonderful player.

N: Now go back to yourself!

J: So the Netherlands String Quartet went on until 1969. And then Friedel died and Paul was getting into a deep depression. He was a child. He never read a book. He hardly read the newspaper. His music was everything. So, when she died he was lost. And the man who took care of him was Everard van Royen – whom you know – of the Muzieklyceum, the professional music school, and the other conservatoire in Amsterdam. Everard van Royen had his ensemble ‘Alma Musica’.

Everard van Royen was a very good flute player and he was interested in early music. But of course – in the way that Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp played early music. Van Leeuwen Boomkamp also played the gamba – but in the modern way. I mean: it was not fretted. He played it like a cello. He had an end-pin and held his bow overhand. He played the Passions, of course, in the Concertgebouw. He was about the only and the best gamba player in Holland, so he did all the Passions. You would not like to hear it now, probably, but he played the gamba. He played with Everard, who played the modern flute, of course – there was no question of a traverse [baroque] flute – and with Jo van Helden, who was my predecessor in the Netherlands String Quartet, who still played some early music as second violin. Paul Godwin was the first violin and Gusta Goldschmidt played the harpsichord. That was the ensemble: Alma Musica. They had a successful career – it was a well-known ensemble. They played many concerts in Amsterdam. Bertus van Lier arranged the Art of Fugue for them. So, they played the Art of Fugue many times.

Everard van Royen took care of Paul when he fell into this depression. And he was helped also by somebody I know well, as a good friend. In the early days, I had been a member of the Rotary Club, but I travelled too much, and so I left the club. About five or six years ago I was no longer leaving the country so much, and I rejoined the Rotary Club, up until last year. I kept a number of friends from it. One of them is a banker, Jeroen Brikkenaar: he lives in Bussum, and he did a lot for Paul. He took Paul into his house, he told me that not so long ago. And he likes music a lot.

N: Did it mean the quartet stopped at that time?

J: No, not quite. I said: It is my time too. When Paul left, I said I will leave at the same time.

N: So, did he leave when his wife died?

J: He left after his wife died. So, I said this is the moment for me, I will leave too. We had wonderful years, but that’s it. Nap continued – we had already changed the cellist, because Boomkamp had decided to stop in 1966. For a second time we spent the summer in Aspen, Colorado, as quartet in residence. That was the year that Agnès and the children came. I think Boomkamp celebrated his 60th birthday then. He was teaching at three conservatoires, and long before he had said: when I am 60 I will stop the quartet. And so he did. It was planned. He was a very good player, but that was it for him. And so we played with another cellist: Michel Roche, who is in Rotterdam. Good cellist. We had a few years with him. After Paul and I left, the quartet continued for a few years with another second violin and viola player.

But, Paul had a come-back. Thanks to Everard and Brikkenaar, and maybe some others. They coached him back to life. He wasn’t playing any more, but he had the opportunity to play the Mozart Concertante with Menuhin. That was in the big hall of the Concertgebouw. I was there. It was fantastic. Since that time I hated Menuhin. He played less well than Paul. For Paul, it was now or never. And he played the viola so well. Menuhin didn’t even stay after the concert …

N: Too professional?

J: It was really inferior character. Although everybody always says: the humanist … Pfff!

But then after that it went bad again. Paul lived for a time in the Rosa Spierhuis in Baarn. But they don’t have psychiatric help there, and Paul needed that. So Van Royen managed to get him into a home in Amersfoort: a kind of centre that has psychiatric assistance, and that’s where he died. Very sad.

Early music

N: What happened after you left the quartet. What did you do then?

J: That was in 1969. I didn’t realize immediately that I needed a quartet. Well, I have to go back in years. I have to go back to 1959/1960, or I have to go back to my little school concerts with Frans Brüggen and Janny van Wering. We even made a little recording, which Frans probably doesn’t want to know about, of Telemann Trio Sonatas, for CNR, a Dutch record company. And then I knew Utti, because I played once or twice with the Leonhardt Consort as a reinforcement in Bach Cantatas, I think it was. So I knew Utti, and then I had the idea of bringing them together: Brüggen and Leonhardt. I knew Anner Bijlsma, because we were playing together in the home of a gentleman who was on the board of the Conservatoire: Halbertsma, a very good amateur pianist. He was allowed by Willem Andriessen to play with the Conservatoire orchestra, on his birthday: the Variations Symphoniques of César Franck, and he played very well. I haven’t heard that piece for a long time – a wonderful piece. So, I got to know the Halbertsma family, because I was then the concert master of the Conservatoire orchestra, and he asked me to come to his home to play sonatas. It was a great pleasure. Probably he invited Anner also, so that’s why I knew Anner. We then played trios together with Halbertsma.

So, I had the idea of getting this together. And we started to play. Utti lived in the Nieuwmarkt and I was still living in the Olofsteeg, very close. Our girls knew each other – we have both three girls; and you are from a family with three girls.

N: Yes, we were nine bilingual girls with musician fathers and French mothers, or Swiss in the case of Marie Leonhardt. We all spoke French and Dutch. It was extraordinary.

J: Then I devised the name Quadro Amsterdam. It lasted a number of years. We played Telemann quartets, almost without rehearsing, at Utti’s house in the Nieuwmarkt. At that time Utti had relationships with Wolf Erichson and then Teldec got interested. So, that’s how it started – the recordings of baroque music for Teldec. We did Telemann: the six Paris Quartets, in two instalments. We did Couperin, Les Concerts Royaux, together with Marie Leonhardt as second violin and Frans Vester as flute player. That was it. There are not many quartets to play. There is a Guillemain, ‘Conversations galantes’, which we played a lot. Then there was a Handel concerto with flute and violin. But it wasn’t ambitious enough to last for a long time. We had our good years. They never talked about it again. I liked it. They were good recordings also. So, that started in 1960, when I was still playing with the Netherlands String Quartet. And playing Haydn with the Quartet, that’s when I thought: I want to do that in a different way.

So, the Quadro played until 1966 perhaps. We had our last fling then. We came to England on a tour, playing at Rugby School, and in a catholic school in the Midlands. And then there was a music critic at the VARA, Henk de Bie. He was at the Conservatoire as a pianist, but he was older than me. He was a very good writer. He wrote very intelligent music criticism in Vrij Nederland – a regular column. And he knew me and he loved early music – not all music critics do – but he then sponsored and was active in organizing this. Television was starting, and there is a television film about the Quadro Amsterdam. You see the life of the four of us at home, how we live, and then on the boat to Harwich, and trip to England, because they sent a camera-man with us to England. I have it on DVD.

N: Oh, we want to see that!

J: I think back on it with great pleasure. But the others don’t, because for them this was not important. They all made their own big careers – Brüggen and Leonhardt and Bijlsma. I didn’t do it the same way. But it was great fun. So that was in the mid 1960s and still playing with the Quartet.

R: Can you give a percentage of how much you played with the Netherlands String Quartet?

J: How much in time? Well, we didn’t rehearse that much in the later years. I stopped playing in the orchestra in 1953, because my teacher Jos de Klerk died and I applied for the job at the Conservatory and became a teacher there. So that meant that I had much more time. I fell down a lot in salary, but I was much happier. Still, with the Quartet we earned nice fees – from America I brought back some good money that I was able to use to buy some bows. Then in the course of the years I got a better violin, and then another violin, until I ended up with the Gofriller.

So, timewise I was not so engaged with the Quartet. But we had tours in America, with the usual repertoire. We played some contemporary quartets. That’s another story. Kees van Baaren was a very good composer, but very advanced. He wrote a string quartet for us. You can imagine the face of Godwin receiving the part of this quartet. He was completely lost. Also, the way he composed it – you had at certain moments to come in, and you were free to come in at certain moments. I liked it – but I had to get used to it. What I had to do was to write a special part for Paul with, instead of the freedom of silences, a number of bars. He continued to count. So, he played his notes and he played them well. At one rehearsal Kees van Baaren came to listen to us and Paul made sure that he was sitting opposite him, so that Kees couldn’t see his part. So, we played that a number of times, and also Guillaume Landré, Lex van Delden, Willem Pijper – we played the last quartet in London, in 1953 or 1954. The first concert ever in London, I remember. It was a kind of exception: in Red Lion Square [The Conway Hall], with mostly English ensembles playing there. And then we played on BBC radio, every time. It’s a pity that all those recordings are lost. I know England fairly well from that time.

So, where am I now? I started the early music, the Quadro, seriously around 1960, when we still had the Quartet. So, I divided my time.

N: But this was on modern instruments?

J: The recordings of the Telemann and Couperin were on modern instruments, and with Frans Vester playing on a modern flute. But you know that’s fine.

N: I completely agree. I just think for the purpose of this interview it is important to mention this.

J: Then in the early 1960s I remember I played the Bach sonatas for violin and harpsichord with Janny van Wering, I think. I was not completely satisfied, because of the ensemble sound. For some reason I didn’t get into the harpsichord sound. So, that was the direct reason for saying: ‘I need a baroque violin, I will try to do that’. So, I went to Max Möller – he was very friendly with me, I am very grateful for that – and said to him: ‘Can you find me a baroque violin?’

N: Had you ever heard a baroque violin by then?

J: Well, I had heard Marie Leonhardt, of course. The Leonhardt Consort was already active on baroque instruments. And so I asked Max: ‘Can you find me a baroque violin?’ and he said: ‘Oh, give me six months.’ And then he found me a Januarius Gagliano with the original neck. I had it for a long time. I made recordings with that. So, that was fantastic and I started to find out how you have to handle that. The bow-making was not yet there, but Max provided me with an old bow that I still have. It is a curious one – too curved almost, and too long. I don’t know whether it is really a violin bow. So, that was the first one. And then the making got better. In any case, I had an acceptable baroque bow.

But that was not with the Quadro, which was with modern instruments. After the Quadro ended, and the [Netherlands] String Quartet, I was there with my baroque violin. I played with Anneke Uittenbosch, Frans Vester, who had started the traverse [baroque] flute, and Veronika Hampe. So, that was my first early instrument ensemble. I recorded the Bach Sonatas with Anneke for Columbia Records. It didn’t last a long time, that duo, but that was a wonderful experience. She had a harpsichord made by a Norwegian friend, Ketil Haugsand. It was a very good instrument. Maybe she still has it. And we made a trip to America, using everything I knew from America. I had lots of addresses and a friend there who helped me. So, we made this trip to America in 1970. It was a great pleasure. We had lots of fun.

R: What was this ensemble?

J: This was the ensemble with flute, violin, gamba, and harpsichord.

N: It didn’t have a name, the ensemble?

J: Yes. Diapason 422. I always invented the names for the ensembles. Quadro Amsterdam: I made the brochure, which was very nice, with an old etching of Amsterdam. And then Concerto Amsterdam. Because a few years later, Wolf Erichson started with the Quadro, but he also needed Bach cantatas. We played a number of cantatas with modern instruments. That was with Concerto Amsterdam. And then we did a number of Concerto discs, before we changed to baroque instruments. That was in the late 1960s.

In any case, Diapason was the ensemble that followed the Quadro. But I found I still needed a string quartet. And then I thought, with my experience of baroque instruments: Haydn and Bocccherini and all these quartets. What did they know? They knew baroque music. So, I have to pick up Boccherini and Haydn from where they lived at that time. And then I found Alda Stuurop and Wiel Peeters. And then I tried to reach Jaap ter Linden and didn’t manage. And then the second choice was Wouter Möller. So he became the cellist. And we simply worked. I had to teach; Alda – I don’t know what she did, maybe she was teaching as well; Wiel Peeters didn’t teach; and Wouter – I don’t know what he did. We worked really for a whole season in the evenings, without playing concerts. So we were very well prepared. And we had our long discussions, a bit too long sometimes for my taste. Wiel Peeters especially, he left first. He was a good friend, but he refrained from playing. He didn’t dare to play a note, because he thought it wasn’t good enough. He was always thinking … he wouldn’t go for it. We had to persuade him. We still played with him on the first recordings, the Haydn opus 20, which was taken by Wolf Erichson. That was the first recording we did – in the Doopsgezinde Kerk on the Singel [Amsterdam], and that turned out to be a big success. I didn’t feel immediately that that’s what I wanted. After the experience of a modern quartet, I felt that we were still too tentative. But, in any case it was a big success because it was something completely new: a string quartet with the original sound in mind. It was even made into a CD. It has been on sale for a long time.

After that, continuing with Erichson, we decided on Boccherini opus 33, the six quartets, on two LPs. For that one Dieter Thomsen came from Berlin and Edda Faklam, the one who cut the tape. That was very carefully done, engineered and that has been turned into a CD. So, that’s how the Quartetto Esterhazy started. After this interval. For some reason the Diapason ensemble with Veronika became a bit difficult. We had a few good years. But then I was as happy as can be with the other quartet [Quartetto Esterhazy]. We started working on early Mozart. We made a recording with Erichson of early Mozart quartets: K 156, 168 and 173. And we played concerts of course. We played concerts in the small hall of the Concertgebouw. That was the beginning of public concerts with this original quartet sound. And I do remember that because I had played so many concerts with the Quadro, so I knew the Brüggen fans were coming to our concerts, because they knew what was going on. That was when there was a kind of civil war in the audience, because the quartet series in which we were invited to play brought in the traditional quartet lovers; and we had the young people who were in fact more like Brüggen’s followers. Half of the people left in the intermission, and the other half came and said: now finally! So, it was interesting.

We had a number of years in front of us with concerts, mainly in Holland in fact. We came to England and in Germany. With the Quadro we had travelled in Germany. I have one funny story: typically Leonhardt. We played in a place in the middle north: Westphalia. We were staying in a hotel and eating there together, by the river Weser. We had a good meal and Utti ordered for his dessert a Brennendes Iglo which of course involves ice cream flambé. Utti chose to have it made with rum. So, Utti got his Brennendes Iglo. And after that we had to pay and Utti looked at the bill and the waiter asked: ‘Yes sir, what is the matter?’ ‘Well, it says Brennendes Iglo and then rum, 5 Mark, but that’s not correct because on the menu it says Brennendes Iglo and that includes the flames, so you can’t charge extra for the rum.’ Well, he got it changed.

N: Was he quite mean with money?

J: Oh yes, very.

N: He didn’t want to spend money?

J: No.

N: That’s why he was rich

J: But he was right. He wouldn’t have complained if he wasn’t right. So, where am I? The Quartetto Esterhazy. So, then we worked towards the big Mozart quartets. That was mostly our task. And then Concerto Amsterdam changed over to baroque instruments. That was in the 1970s.

I played a Leclair concerto. That was the first thing I did with Concerto Amsterdam. There were about 12 players. Three first, three seconds, two violas, two cellos, a double bass, and a harpsichord: a very nice ensemble, with more especially for recordings. I am not an organizer, but we did manage once to play three concerts for the Amsterdamse Kunstkring. It took me a lot of time. Kirchner was the man I knew who organized this. So, not many concerts – but recordings, yes: Leclair concertos and then other things.

Concertos with the horn player Hermann Baumann and Quartetto Esterhazy also played chamber music with Baumann. So that was very interesting.

We went to Italy with the Quartet, because we had friends there. There was an Italian in Padua who was interested in us and organized concerts. So several times we travelled in the north of Italy and then we got a concert in Naples. That was our last concert. Wiel Peeters dropped out fairly soon. He made a number of recordings. And then he told me that he wasn’t able to continue. It was psychological.

N: I had no idea.

J: He was not comfortable at all playing this viola in public. I regretted it. But then I heard lately from somebody that he lives in Tuscany with his wife, growing olive trees. He lived in Sardinia for a number of years and then moved to Italy to Tuscany.

But, in any case we needed another viola player. And the one we got was Linda Ashworth: an American and a very good player. She was the concert master of the Ballet Orchestra and was willing to take up the viola. And she did very well. With my viola, which is a smallish instrument, not a big one. So, the rest of the time with the quartet she was the viola player. So we had Alda, Linda, and Wouter.

We had made a number of recordings. The Decca producer was Peter Wadland, who was the main producer for L’Oiseau Lyre – early instruments, The Academy of Ancient Music, and so on. He invited us to come and record the six ‘Haydn’ quartets of Mozart. We did it at Aldeburgh, in the Snape Maltings concert hall – a wonderful hall. In the same place, later on, I recorded the quintets with the Smithson Quartet. So, we recorded the six Mozart Quartets. By then AAM was already doing lots of baroque music. Wadland had in mind to go on to Mozart. And he was considering me as an inspector, as a leader. But he wanted to know if it would fit together. So he invited me to make a recording of the six Geminiani Concertos, which we did in Hampstead in Rosslyn Hill Chapel.

That was the first time I worked with these people, and everybody liked it – I liked it, they liked it. That was the moment when Peter said: I am considering a big project with the Mozart Symphonies, would you like to lead that? So that was probably in 1977–78. (Although when the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century started in 1981, Brüggen presented it as if they were the first.) The system was that we did two weeks of recording: two days of rehearsal, paid by Decca – which was a first, and the only time they did that – and then the rest of the two weeks, the batch of symphonies. That was in 1979, I think. It was nice because we rehearsed and everybody could contribute. I was standing up, and that’s where that television programme is from, in that first batch of symphonies. I was standing in front of the orchestra and that is much better than conducting. There I am with the bow. And I indicated my bowings and I had prepared the scores. So, that’s where my French background comes in: the way I use the bow.

N: I remember that the bowing exercises that you made me do for years were by Catherine. I had to start every lesson with these bowing exercises.

J: They were very good. I mean, Sevcik is useful – you can learn something – but deadly.

N: So boring.

J: I got that from Pasquier.

N: I have occasionally taken it out for students and I think it is really good.

J: It is. That’s where I am different from the other ones. So, in any case, that was very inspiring. Everybody liked it.

Now I am at the end of the 1970s. The Quartet still did a few concerts but I was looking forward to the end of that. We finished the six Mozart quartets, and then Decca wanted to do the quintets. We managed to do one recording of that: the G minor and the C major. Wonderful pieces. We did that at Kingsway Hall. It is an LP. They converted the quartet recordings to CDs and they were on the market, but never the quintets. The American engineer who has worked for us, Peter Watchhorn, had time and he put it on a CD. Both the quartets. I love them both, but that’s the end of it. And then we played a few concerts in Italy and the last one was in Naples.

N: See Naples and die!

J: And then stop playing. So, that was the end of it. I was sad but also relieved.2

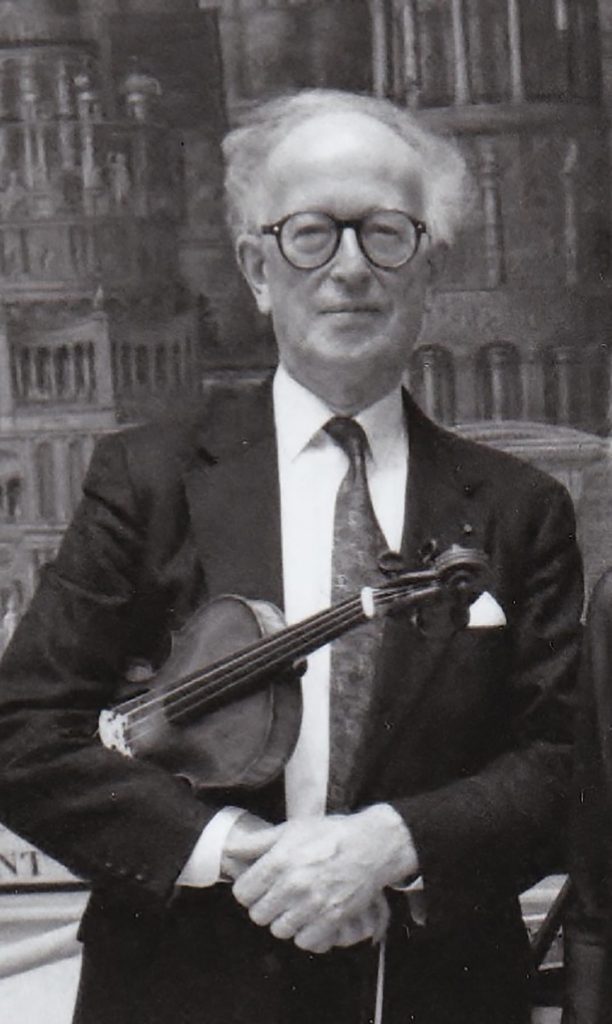

(photo: Schröder family archive)

USA

The Netherlands String Quartet had played in America almost every year until 1969. Then I had Diapason 422, and we made one trip to America with that ensemble. Then I was asked to come back to Aspen, which is the modern music festival of the Juilliard School, and where we had spent two summers with the Quartet, 1964 and 1966. This time was the beginning of my baroque playing and the Esterhazy Quartet, and they asked me to come with the baroque violin for a tentative period of two weeks. It wasn’t really a success; it was too early in fact. But, I met a harpsichordist, Helen Katz. We played together. She was very much in favour of this. That was the late 1970s. She was very well acquainted with my dear friend Albert Fuller. And he was planning a baroque festival, for the first time in America. He was a harpsichordist and teaching at the Juilliard and really thinking about developing this early music scene with at least two violins. He said: baroque music, if I organize something, I need two violins. And he knew one already: Stanley Ritchie. So Helen Katz said: you have to ask Jaap. He wrote me a letter – I still have it – ‘Dear Mr Schröder’. He was always very flowery in his language. So I was invited in 1973, for the first Aston Magna Festival. So, that was another beginning.

The festival ran for three weeks in the Berkshire Hills, between New York and Boston, close to Tanglewood: a private estate and a beautiful place. There had been a famous violinist there, Albert Spalding, who had a wonderful house and estate there, which was bought by a banker who loved baroque music. He gave Albert Fuller the permission and money to organize this first baroque festival, and Albert always had wonderful ideas. He said it should be three weeks with concerts. So Stanley Ritchie, the second violin, was there, and a cellist and some wind players – John Solum was the flute player – and a few more. But, it was not only concerts. You could come as a postgraduate student and get lectures from a specialist about a certain theme. From the first year onwards Albert gave each summer a name. I don’t remember the order, but one was Versailles. We had an architect talking about the architecture in Versailles, and French literature, and of course French music. So the concerts were combined with in-depth lectures on the period. Another theme was Thomas Jefferson and his time. And of course we had Italy. It was wonderful to concentrate on certain subjects. And Albert was the man behind the whole thing, not only playing the harpsichord. These were fantastic years. They lasted from 1973 until 1981, and then it changed; but that’s another story.

In the first festival we did the six Brandenburg Concertos, which then two years later – I think in 1975 – we recorded. Albert wanted to do that. So we recorded it and then he had to find a label to publish them which was quiet difficult. He was a bit disappointed that it wasn’t done by a big label, but by the Smithsonian Institution. The man there, Jim [James] Weaver was a former student of Utti. Jim Weaver managed to have the tapes bought by the Smithsonian and that’s where it was published. We played them in concert there and also in New York in the Metropolitan Museum. We had several years of concerts in the Metropolitan Museum.

The first three years we had Shirley Wynne and the baroque dancers. Ah, she was a wonderful person: very intelligent, but also lots of taste. She didn’t dance herself but was instructing the group of younger people, one of whom is still continuing the New York Baroque Dance company: Cathy [Catherine] Turocy, who is married to a harpsichordist Jim [James] Richman. Since my bow was my life, I was delighted to learn so much about moving and dancing. Shirley started every morning for the whole group of students and teachers with an hour of baroque dance step. And then in the programmes that we did, with Rameau mainly, I was finding out the best bowings to accommodate the dancers.

I kept in touch with a few of those dancers. It was a wonderful atmosphere. And with Albert it was always such a feast to be there for three weeks. And then during the year I came back for concerts in New York. He had a wonderful studio. He had good friends with lots of money. He was teaching at the Juilliard, but that wasn’t giving all the money he needed. He had a childhood friend, whom I knew also, who loved music and who gave him this studio to live in – a fantastic place, near Lincoln Centre on West 67th Street, between Central Park and Columbus Avenue. It was the centre of activities for him and he organized concerts there. And he rented it out for a film called All that jazz. One ceiling had been broken away. He lived on the first floor and downstairs was a big studio.

Well, Albert died some years ago [ 2007 ] and the apartment has been sold. But when I am in New York now I am sad because of that.

We were also invited to play in Tanglewood. That wasn’t a big success, because Tanglewood wasn’t ready for early music. It was the Boston Symphony who played there with Joseph Silverstein. He pretended to be interested, but it was not his cup of tea. But we played a number of concerts throughout the States.

After six years Albert said that after the baroque he wanted to go on to early classical. But the board of directors didn’t want to. They said: this is successful and we have to continue. So he broke away. Very sad. He started his own series of concerts in his studio – as the Helicon Foundation – and I was part of that. I left Aston Magna with him and moved to the New York scene.

The Helicon Foundation still exists. I did many concerts there, also with Penny Crawford, and went on in the repertoire, which was what Albert wanted. He himself didn’t play there. But he had a really wonderful mind. I am still in touch with the man who took care of him when he was getting ill: an oboe player who lived there, because Albert needed help. He was very ill at the end. Albert and many friends were part of the homosexual scene there. I never felt the least inclination for that. But he was not at all irritating. I accepted that from him.

The Diapason ensemble had an American tour in 1970 or 1971. We had an invitation from Jim Weaver at the Smithsonian in Washington. So, we played there and that was the beginning of a long link with the Smithsonian.

N: Was it the time when the Strad was restored by Lindeman?

J: That is in the Metropolitan in New York. That instrument I played. I even made a recording with some of the solo pieces on that Strad. But the Smithsonian has a very, very important collection of instruments. Partly their own, partly those that belong to rich people who have the money and the interest. There was a Stainer quartet, and there were other Strad instruments, and they were in the Smithsonian, on the fourth floor, I remember very well.

We played on them in the museum. But they rarely went outside, because these instruments were not insured: it would have been impossible. There was an enormous number of guards. It was very difficult, even when you brought in your own violin: it had to be checked and registered and so on. So, instead of paying a huge amount to insure the many very valuable instruments, they paid for guards.

We rehearsed regularly there, and we made some recordings. There were exceptions – I don’t know how they managed. We did take them outside to Annapolis to do Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, for instance. That was great – a wonderful piece. But it started with simply baroque concerts – with Anneke Uittenbosch – and then I continued going there. I met Marilyn McDonald, who was a baroque soloist there.

The Esterhazy Quartet had stopped in 1981, and I was already playing baroque concerts in Washington. So, what was more logical than with the friends there to say: would you like to make a string quartet? This was Marilyn McDonald, Judson Griffin and Ken Slowik, the omnipresent cellist who was organizing things at the Smithsonian. (Albert Fuller wasn’t especially in touch with the Smithsonian. He had his reservations about a relationship with the people there.) So then from 1982/1983 on it was the Smithson Quartet. We started with Haydn; I don’t think we ever played Boccherini. But then we did Beethoven. And I think our very best recording is the Opus 18 quartets by Beethoven. We did that in a famous [Merkin Concert?] Hall in New York City.

N: How often would you be going to America?

J: Say four times a year, because I was also teaching at the school of music at Yale. I had an appointment for four visits a year. Two weeks each, or so. And I combined that with the Smithsonian. I went from one to the other. And then I also had some concerts throughout the States. The Yale connection has always stayed. At Yale I had an open roster – everybody could come and play for me. I had a trombone player there who signed up for a lesson. I was wondering what he was going to do; he played a preludium of a cello suite by Bach. He articulated very well. But it was violinists, first of all. They played all the Bach, of course. We discussed Bach, and some of them liked it very much and others said: well, no that is not my cup of tea.

I had a good time there. But, of course, I was the exception in a modern world. I never managed to have any vocalists there for a Bach cantata. In the last two or three years it has changed. They have felt that they have to get up to date. There is a violinist, Robert Mealy – I haven’t really known him – in Boston, and he is now the man who is really organizing things at Yale. So I combined Washington and Yale, together with Albert and the Helicon Foundation in New York. I was really spending part of the year in the States.

And then, I have to get to the Atlantis Ensemble. Of course, I played concerts in France now and then, and I recorded Mozart Sonatas with Lambert Orkis in 1989 and in England. I got the Smithson Quartet to France for a few concerts and then I started the Atlantis Ensemble. I called it Atlantis because it was composed of some European members and some American members, so a kind of combination across the Atlantic. It was first of all a trio with Penny Crawford (fortepiano) and Enid Sutherland (cello). And so we played in Ann Arbor, Michigan. And then we started doing some recordings, not yet with Peter Watchorn. We did the Schubert Trio with this fellow from California [David Cerutti, viola] and that was it. We wanted to do other things that involved a few more musicians. In concerts we played the Trout Quintet, the Schumann Piano Quintet, and things like that, and we continued to play Beethoven trios.

And then Peter Watchorn came into the picture. He started the Musica Omnia label and wanted us to do chamber music with piano – the Graf grand piano that Penny owns, a unique thing from 1835 in mint condition, well cared for. She paid a lot of money, I think, for the upkeep. It didn’t have to be restored but it had to be worked on every time we made a recording. It sounds great. It is a wonderful instrument. So, starting with Schubert, the Trout Quintet, Schumann … in the last couple of years we did Mendelssohn. A Mendelssohn album with wonderful music: his Piano Quartets, opus 1–3. This is great music. I knew the Violin Sonata in F minor, opus 4, and that is also a great piece. He was 14 years old when he wrote it. The Piano Quartets with this old piano: it is of course such a better, transparent sound. So I have worked with Penny for a long time – concerts and recordings. The Smithson Quartet was going full swing until the Reagan years, when the money dried up. That was around 1996. Ken Slowik could no longer organize concerts in Washington – we had had a series of concerts at the Smithsonian every year. So that was the end of the quartet.

Iceland and recent recordings

A number of years before this I had been invited to Iceland by my student Svava [Bernharðsdóttir]. I had met her at the Juilliard: she was studying there, had listened to my lecture about early music and had said: ‘Ah that’s what I want to do.’ So she came to Basel to study with me. Basel started for me in 1973/1974 thanks to my friend Michel Piguet who was teaching the oboe there. He introduced me to Peter Reidemeister, the director. They had started a new existence, so to speak. The Schola had been there since 1933, with string players – well, August Wenzinger was the gamba player. The violinists were modern players who put on gut strings, and still with the chin rest and everything. For some reason that had stopped and Peter Reidemeister asked me to come in. So that went together with the Esterhazy Quartet. With the Smithson Quartet we played a Haydn programme in Basel once and we gave some classes.

In Basel Svava then said: I have to introduce you to my friends. We have a baroque ensemble in Iceland. This was more than 20 years ago – perhaps 1989. That was all baroque: the Bach Consort. And I played the Bach Sonatas with Helga [Ingolfsdottir]. We did some recordings there. I was very happy with that. We did a Vivaldi programme with different concertos: the cello concerto with Sigi [Sigurður Halldórsson], the two oboes concerto, and I played a violin concerto. It was very well sounding and with good people. They really were eager to do this. So that developed. So, when the Smithson Quartet stopped, the same story repeats itself. I asked them: Are you interested in playing quartets? So, with those people I formed the Skàlholt Quartet.

Skàlholt is the church outside Reykjavik, an hour and a half away, in the open country. It is where the very first church was built in the year 1000 or even before. There is a new church there now, built in 1953 through the efforts of a wonderful man who was the initiator of all this: the bishop of Iceland, and a grandfather of Svava. So, I got to know him and his wife and some of his eight children. Svava’s mother was a daughter of the bishop. Every time Agnès and I came to Iceland we were received in the house of this man, Sigurbjörn Einarsson. Wonderful people. So, we did baroque music for a number of years. We did an English programme. I had devised a programme with theatre music by Purcell and other English composers. That’s a very good disc (Theatre Music in 17th Century England). The sound in that church is fantastic.

So the quartet started very modestly. Not much time. But the musicians are fantastic. Soon they really got it. We played Haydn first of all. And from Haydn we did Mozart, and then we moved to Schubert.

With the Esterhazy Quartet and the Smithson Quartet it was also research – from the early Boccherinis and we even played a Tartini with Esterhazy (a Sonata à 4) – an ongoing research on how we play the young Haydn: what did Haydn hear in his ears? We tried to find out; and then moved on to Beethoven and then finally to Schubert. So, now we are in the stage of that research and doing the Schubert quartets. And then we will go back to Haydn opus 76. But, I would love to go on to Brahms: to play Brahms in the way I hear it. With the Nederlands String Quartet we played wonderful Brahms, but it was modern Brahms. So the Skàlholt people are very happy. We make some recordings, we have a few concerts here and there: not much.

That’s where I am now.

The Atlantis Ensemble did the Mendelssohn album (three discs), and the Clara Schumann piano trio and the first of Robert Schumann’s trios: a very nice disc. Clara Schumann was a very gifted player. Then the last disc that came out is the Schumann piano quartet together with an unknown trio which I found in Washington in the library.

You know one of those great virtuosos of the nineteenth century, besides Liszt and Chopin, was Sigismond Thalberg. He was the great competitor of Liszt. The two of them were really jealous and fighting each other. Thalberg composed mostly fantasies on operas and he composed one piano trio. It is almost a bit like Brahms: very good music and nobody knows it. So, that is on this Schumann quartet disc. That was the most recent thing we did. And now the latest thing is the Kegelstatt Trio [Mozart], which we recorded at the same time as two piano quintets of Mozart and Beethoven. But Peter plans to put the Kegelstatt Trio together with the Clarinet Quintet.

Owen Watkins is the clarinet player, also an Australian, like Peter. He lives near Boston. He works at the workshop of the recorder builder in Boston, Von Huene. So he repairs and builds instruments. He has a collection of old clarinets and he is very expert in all this. And he plays wonderfully.

With the Skàlholt Quartet I have recorded a programme that includes a Haydn that is a single opus, opus 42, together with the last two Boccherini quartets: very interesting material. And a Michael Haydn divertimento. And, I still have to edit, to listen to all that material.

With the Bach Consort we did a programme of early Italian stuff, seventeenth-century string music. It is in my room waiting to be treated: a lot of work.

So, the Beethoven opus 18 quartets (with the Smithsonian Quartet) have been reissued, because they were very successful.

Oh yes, and then there was Jos van Immerseel. He wasn’t teaching at Basel, but I invited him to do Mozart Sonatas there for the Schola Cantorum series, so we recorded two discs of Mozart Sonatas and then Reidemeister asked us to do the whole series of the ten Beethoven Sonatas. We recorded in Antwerp with the Graf piano there. They reissued them also in 2010.

And with my friend in Sweden, Kjell-Ake Hamrén, I did six violin duos by Gasparo Fritz. He was a Swiss violinist in the eighteenth century. Classical, no longer baroque really. And it is very nice music. It was just great fun to do it with him. He is a good player. We did it in a small Swedish church, and he edited it himself.

With the Skàlholt we played in the Esterházy palace, in 2009. The concert was recorded by the Hungarian radio and I got a copy. It is very nice; it could be a disc. Haydn opus 9 and 17, and starting with Boccherini. And then, we recorded the Seven Last Words in 2009 and that is out officially.

And I made a disc with the best student I ever had in Basel, Dana Maiben, an American. She works in and around Boston and organizes concerts. We made a disc of Purcell and Bononcini trio sonatas, for a special reason. Bononcini is from the middle of the seventeenth century. He composed a lot of chamber music and these trio sonatas belong to more than one opus. He worked in Modena, where the Este family reigned. The Princess d’Este got married to the Duke of York. She was a great music lover and came to London and took lots of music with her. And that is the reason why I said to myself: Purcell may well have heard this music by Bononcini. It goes very well together, so I put together a programme of the two. It is with Dana and Alice Robbins, the gamba player from Boston, and Meg Irwin-Brandon, who I have known for a long time, a harpsichordist/organist near Springfield. A very nice person. I still play with her occasionally in Davenport College [of Yale University] when she is there. I was very happy with that disc.

I made a solo violin disc in Skàlholt. And I made an Italian disc in Naples with friends from the Naples orchestra – not that good. The engineer there wasn’t very good. Whereas the Vivaldi concertos in Skàlholt – that was very good.

Mendelssohn trios we did, of course: both of them; and also Fanny Hensel, the sister of Felix, who wrote a very good trio. She was a gifted composer. She was allowed to be a pianist and travelled with her brother to Italy, where she had great success. That gave her confidence. So when she came back to Berlin she insisted on doing a bit more. But the family didn’t allow her compositions; they were hidden in the family archive until two years ago. In Germany there is an association of women musicians and they have been very active. So, the piano trio is a wonderful piece.

And in France I made three discs with violin sonatas for a French label: a whole disc with Mondonville, and then Marais combined with others – including de La Guerre.

And the Schubert Octet. It was one of the first things I did. I had played it already with Penny Crawford. But then I had in mind I would love to do the Schubert Octet. It was a real Atlantis project. I had Jaap ter Linden with me, and Hans Rudolf Stadler the fantastic Swiss clarinet player, and Judson Griffin the American viola player, and Carol Harris an excellent violinist and a student of mine at Yale, and the horn player (Lowell Greer) was American. So, it was a real mixture. We rehearsed for a week in Les Mûrs [the family house of Agnès Schröder]. We had a fantastic week. And then recorded it in Germany. It was released by Virgin Classics in 1990, and is no longer on the market. Peter Watchorn would love to have it in his repertoire.3

I started playing the violin when I was 8. So it is now about 80 years. I think I will call my book: ‘80 years of violin playing’. Because it will not come out before I am 88.4

In later life (photo: Schröder family archive)

Membership of music groups

1952–1969

Netherlands String Quartet

1960–1968

Quadro Amsterdam

1961–1978

Concerto Amsterdam

1972–1982

Quartetto Esterhazy

1974–1990

Schola Cantorum Basiliensis

1976–1987

Aston Magna Ensemble (later Helicon Ensemble)

1977–1985

Academy of Ancient Music

1982–1996

Smithson String Quartet

1984–1996

Smithsonian Chamber Orchestra

1988–

Atlantis Ensemble

1993–

Skálholt Ensemble

1996–

Skálholt String Quartet

Notes

- In a fragment of our interview, Jaap remembered the Andriessen family and went on to talk about his own religious faith:

J: Laura, a sister of Willem and Hendrik and Mari, even another brother who was an English teacher, another Andriessen, oom Kiek [Nicolaas]. Oom Kiek for a time lived in Utrecht in the home of his brother Hendrik. The story was, that somebody rang the bell and oom Kiek opened the door and there was a man filled with awe and he said: Mr Hendrik? and oom Kiek said: yes, I am Andriessen, but I am not Hendrik and the man said: O you are not? then you must be Willem Andriessen? and he said: No sir, I am not Willem Andriessen. But then you are Mari Andriessen. Afterwards he said: I am fed up with being a brother. They all had the same sense of humour.

I went very often to Haarlem. This is something that seems to happen. I am an only child, and only children often look to be with families with many children, for the sociability and so on. Mrs Andriessen was a wonderful woman. It is a catholic clan, but Mrs Andriessen at that time, I would say was very liberal and I liked that a lot. There was an atmosphere of conservative catholicism at this time – for Agnès it was horrible and for me too. It was awful.

N: It was Holland. Catholicism was very conservative

J: Well it was everywhere. Have you heard of the ‘mandement’ – a sort of edict published by the bishops. It was forbidden to be part of the socialist party and that kind of thing. It was horrible.

I myself had lived in Paris for two years and was part of the university community and there was a priest there who was a fantastic man. Before I came to Paris I was interested. My parents were not religious really and I was reading – there was a war paper edited by a liberal catholic group. I always had in mind: you have to be catholic and communist. That combination I can see. I once talked to a priest in Amsterdam and it didn’t last for more than five minutes.

But then in Paris I found something completely different. The man there had been in the scout movement and he was not only a very deep-going priest but he was also an intellectual. He had finished the Polytechnique and so he was surrounded by this whole community of students. I became part of that and I got baptised there in 1949. But then coming back to Holland was absolutely horrible. Now the church is falling apart – I read about it, but it doesn’t affect me, I don’t feel part of that. I feel part of the French. - We also recorded this fragment in which Jaap said: ‘The Quartetto Esterhazy made one trip to America, in 1974. We were successful in Holland and I knew the people in America. There was an American manager: he was also an oboe player, and he had a group that involved some players. Albert Fuller wasn’t playing with him but they knew each other well. And so I was asked to play with him. and he wanted to organize the tour for the quartet. It was an extensive tour. It didn’t give us much money. He was clever enough to pocket that himself, probably. The concert organizers were paying him. But it was wonderful because we had lots of excellent responses and played at New Haven, at the collection of instruments. It was the first time: string quartets with the sound of the original composing, and so it was important. But we never got to a second trip. I don’t know why – perhaps just because the Americans didn’t find the time or the interest to do it.’

- Otto Steinmayer’s Schröder discography, which catalogues his recordings up to 2006, is here.

- Later in 2012 Jaap Schröder recorded an interview in French that is published on the Muse Baroque website.