Back to Journal

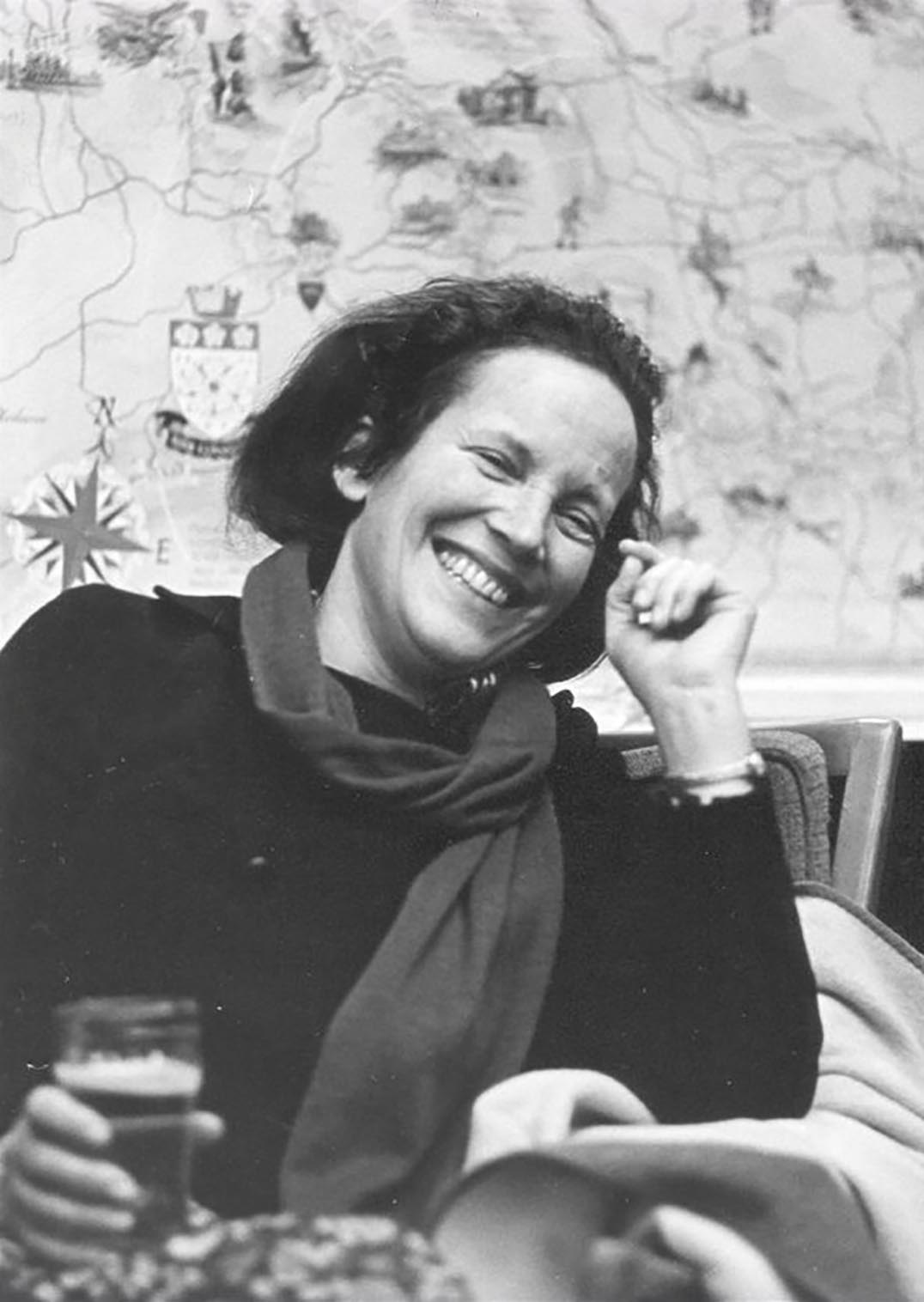

Marie Leonhardt-Amsler

Marie Leonhardt-Amsler died on 23 July 2022. In 1996, when I started The Bach Players, Marie and her husband Gustav Leonhardt, who pre-deceased her in 2012, agreed to be patrons of the group. There was more to this than just the wish to associate two famous and inspiring people with my project.

I grew up in Amsterdam, at exactly the same time as they were raising a family of three daughters. Our family also had three daughters, and we all knew each other. I remember Marie as a warm welcoming presence. For birthday parties she would string wool around the legs of the various harpsichords in their house. We had to follow those threads – and discover that there were bars of chocolate at the end of them.

As a student I came to live, as an anti-squat guard, in a superb house on the Herengracht in Amsterdam. The Leonhardts lived behind this house (in the ‘achterhuis’). By that time I had made music my profession and had started to explore the baroque violin. How lucky I was to live next to Marie, who was so supportive to me and to the younger generation of baroque violinists. Her enthusiasm for the music was infectious.

She was the lead violin of the Leonhardt Consort. Her playing was strong, persuasive, and full of zest. In the great project to record all the Bach cantatas (1971–1990), shared between Gustav Leonhardt and Nicolaus Harnoncourt, Marie led all the cantatas that Gustav directed; Alice Harnoncourt led the cantatas for her husband. I was just old enough to have the luck to be invited to join the Leonhardt Consort for some of the last of these recordings.1

Marie and Alice were friends – and Alice died three days before Marie. Two giants of the twentieth-century Early Music revival movement have gone together. They leave behind a very different musical landscape from the one I grew up in.

At the 1980 Erasmus Prize ceremony in Amsterdam, 8 September 1980: Alice Harnoncourt, Marie Leonhardt-Amsler, Prince Bernhard (awarding the prize), Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Gustav Leonhardt. The joint prize winners were Harnoncourt and Leonhardt.

Marie’s funeral ceremony took place in the Waalse Kerk in Amsterdam, where she was a member of the congregation and where for many years Gustav was the organist of the beautiful Silbermann organ. This church was the central venue for their concerts and recordings and for the performances of many Early Music pioneers in the 1970s and 1980s. It was there that I first heard the Monteverdi Vespers being performed. It was there that I heard Jordi Savall and his Hesperion XX for the first time. In my memory the church was always packed. These concerts attracted a young audience who were ready to explore a different approach to music making. Conventional concert dress was disposed of in favour of a more casual dress code. There was a buzz of excitement and discovery.

It was a time when everything was questioned. Amsterdam was a centre of ‘hippyism’. The Early Music movement needs to be seen in this context. It kicked against the traditional classical music concert practices. At that time (and even still?) the programming of the Concertgebouw Orchestra was conventional: overture, concerto, interval, symphony. It was mostly confined to music of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. On any repertoire, including earlier music, twentieth-century performance practices were applied, like a thick varnish applied with a broad brush. Leonhardt and Harnoncourt started scraping at that varnish and proposing a very different approach to performances of baroque music. The music came alive again. It was like listening to contemporary music in first performances. What a wonderful time it was to be a young musician.

And where are we now 50 years later? Music played on original instruments has been integrated into the mainstream of concert programmes. It is no longer a ‘niche’ practice. This is a wonderful development, of course. But what do we see? To be accepted, Early Music has been adapted to conventional concert practices: musicians of the various historical performance ensembles are expected to wear uniforms again – long dresses, white ties and tails. The cult of the conductor is as strong as ever; conductors appear even for repertoire that doesn’t need them. Large concert halls are used for performances of sacred seventeenth- and eighteenth-century music that was written to be part of church services. Only the canon of famous pieces gets performed regularly. Very few promoters are prepared to take risks with their programming.

My thoughts have perhaps wandered too far from my subject: Marie. But I can finish by linking our present situation back to her. Young musicians are still finding ways to experiment and explore, not in copying the practices of the explorers of 50 years ago, but in finding their own paths. And there are still teachers who refuse the idea of master and pupil, but who stand at the side of their students, encouraging them.

————————————————————

Nicolette Moonen

————————————————————

Note

- Nicholas Anderson wrote about the project here. According to the Bach Cantatas website I played on the Leonhardt recordings of Cantatas BWV 100, 107, 113, 114, 117, 127, 128, 129, 132, 133, 134, 135.